Low-level Issues

So far we’ve outlined the high-level design that should help us productionize the text summarization service. But this is not the end. We always advise to start with drafting the high-level design of your solution before going into the details of any separate part of it. You can read more about the motivation behind this advice in the previous sections of this course. However, after coming up with a high-level design, which our interviewer is happy with we will have to figure out some details about it.

In the design above we briefly suggested one possible way to send the requests from the front-end clients to the summarization service. This suggestion was probably the simplest possible implementation - to expose a RESTful API from the service, which accepts text articles for summarization.

There are at least a couple of issues related to this approach. One issue is related to the scalability and the other to the robustness of our design.

Let’s say that the clients send the text articles over HTTP to a RESTful API. If at a given point in time the incoming requests increase, the summarization service may be unable to handle all incoming requests and some of them could time out. This will result in poor experience for the customer.

We could make sure that we have a number of instances that are running the summarization service and put a load balancer in front of them. This will allow us to handle more requests and scale horizontally by adding more instances of the summarization service. The load balancer will route the requests to the instances that are less loaded.

However, there is another problem with this solution. If for some reason an instance of the summarization service is not able to handle requests and a request is routed to it, this request will most likely be lost. Such a thing could happen if all allocated instances are busy with other work. Also, if a given instance is not responding for some reason, due to a bug in the code, or some other issue, we could again lose a request that was routed to it by the load balancer.

Let’s try message queues!

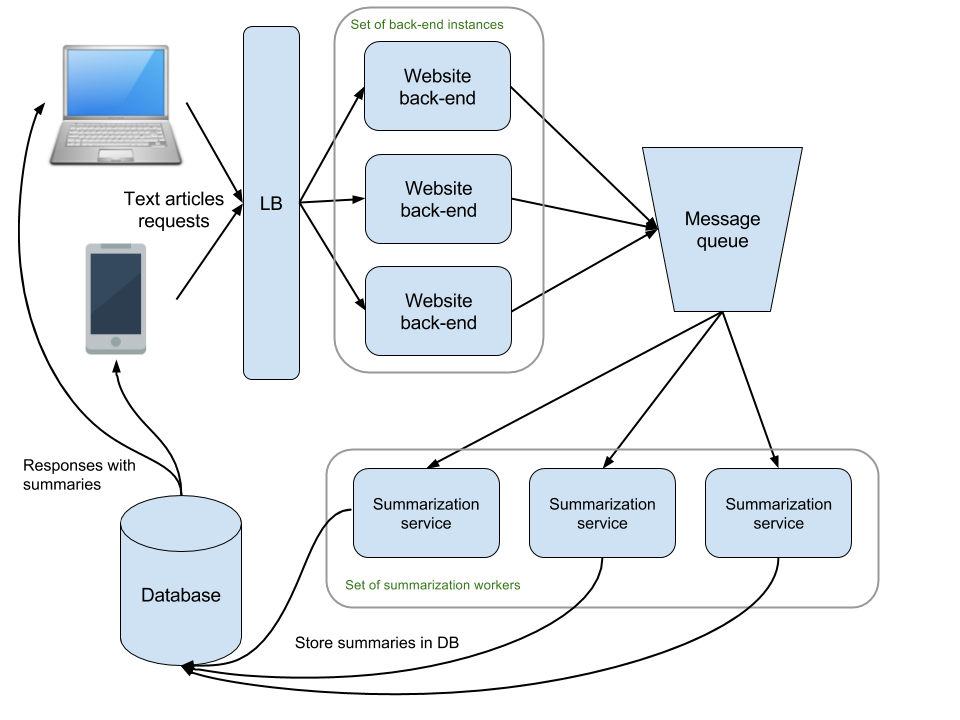

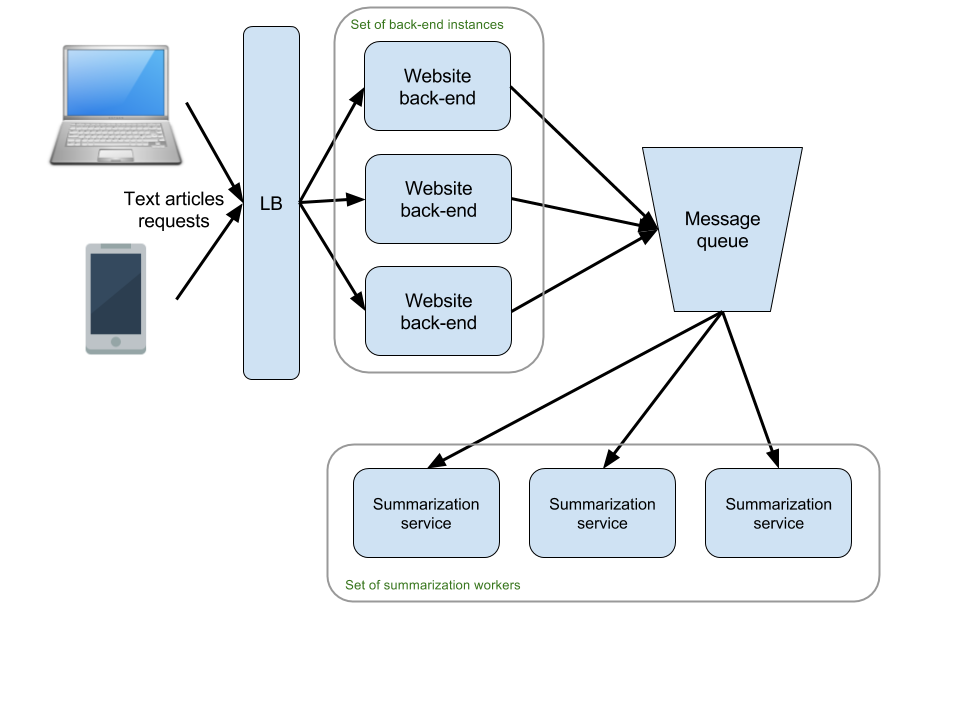

An alternative approach that resolves the issues above is to use a message queue to store the summarization requests. In short, a message queue will allow us to enqueue on it all summarization requests. Let’s call all such requests stored on the queue jobs. Then, if we have a set of workers running the summarization service, each worker could pull jobs from the queue, one at a time. Each job can be processed by the worker that picked it up and the results can be stored in the database.

We will need a message queue that allows multiple consumers to pull messages from it because we will want to be able to start a number of instances running the summarization service. This way we can easily scale up.

Imagine that suddenly the traffic increases. The queue will start to fill up with jobs because the allocated workers cannot handle the increased number of requests. We could have a monitoring service that would detect this situation and would spin up additional workers, which will also start pulling from the queue and will alleviate the load on the existing workers.

Also, with this solution, we know that only properly operating workers will be pulling jobs from the queue. Hence, jobs will not be lost due to not responding workers.

It is still possible that a worker takes a job but crashes while processing it. For example, if we have a bug in the summarization code and it crashes in the middle of the operation. This means that a job was pulled from the queue but a result was never computed. Does this mean that the job was lost? Not necessarily.

We will need to make sure that our message queue requires an acknowledgement that the job was successfully processed. This means that each worker will have to let the queue know that the job that it pulled was processed. If the worker crashes it won’t notify the queue. After a given timeout passes the queue will assume that the job was not processed successfully and will make it available for pulling. This can be done a number of times until the job is discarded to some other place.

As an example, the SQS service offered in AWS, has a default number of retries, currently set to 10. If a job is pulled and not acknowledged 10 times it can be moved to a special queue called dead-letter queue. If such a queue is set up, it can be monitored for failed jobs. It will hold such jobs a given number of days, so that action can be taken on them.

All this helps us make sure that we don’t lose jobs even if various issues occur with our summarization system. These issues could be bugs in the code, problems with infrastructure, deployment problems and so on.

The important point is that using a message queue we achieve two useful things:

- We are ready to scale up easily by spinning up more summarization workers

- We can handle unexpected problems with jobs processing without losing jobs

Finally, how will the front-end clients create the jobs on the queue? Looks like for the website this could be code that runs on the back-end part of the app serving the pages of the website. For the mobile app, it could be enqueuing jobs once a request for summarization is sent through it. This seems like the simplest approach that should work out well given the expected load.

At this point our interviewer could ask us if the message queue could become a bottleneck in cases when there are too many simultaneous requests coming in. At the beginning we were told that we can expect at most 50 requests per second. However, we were also asked to design the system in a way that it could easily scale up if needed. Under heavy load our message queue could run out of connections and become unavailable for some clients. This is an unlikely situation given our constraints and the queuing solutions that exist these days. But let’s prepare for the worst.

To achieve that we could have an additional layer that receives the summarization requests and forwards them to the queue. We already have the website, which sends jobs to the queue from its backend. And it’s a good idea to have this website live behind a load balancer anyway with the possibility to run multiple instances of the website to handle increased traffic. The mobile app could be sending its summarization requests to the backend of the site, possibly over HTTP to a RESTful API. This way there will be one backend with multiple front-ends (web and mobile).

With the load balancer and the ability to spin up more instances of the website backend we could handle increased traffic. However, all this traffic will result in increased number of requests to the message queue, which still remains a bottleneck. Some of the message queues available nowadays can handle a really big amount of messages until they become choked up. With the constraints given in this task we are not even near reaching such a state. Theoretically we could be prepared to run more than one queue that stores jobs, to scale horizontally but this wouldn’t really be needed in our scenario. We are only mentioning it as a possible answer to the bottleneck concern expressed by the interviewer.

In the meantime, we can tune our load balancer to limit excessive traffic to the website’s backend, if this occurs. This way we will make sure that the queue is not overloaded with enqueuing requests. Rather the website and the mobile app will start indicating to its customers that the service is currently overloaded and that they should try later. This is probably the better option than accepting text articles and then failing to summarize them. Here is a more detailed diagram of the design so far.

If you are curious to learn more about message queues, here are articles that we find useful:

- What is message queueing?

- One of the most popular solutions - RabbitMQ - has a tutorials page

Storing the results

We’ve outlined in more details how the summarization requests will reach the summarization service by using a message queue. What we are still missing is how we will store the inputs and outputs and how will the front-end clients retrieve the summaries.

It was already discussed before that we should be fine with using a standard relational database for this. We expect to have at most 12 million incoming requests per year. The total size of the database won’t be trivial but the number of records in it will be pretty modest to allow for efficient querying.

This means that each summarization service instance could write its result to the database once it’s ready with the work. This would mean that we have multiple instances writing to this database because we plan to have multiple summarization workers handling requests. This should be fine as long as we don’t have too many such workers, which occupy all available connections to the database. With the expected load we should not be in such a situation any time soon.

An alternative would be to let the workers write their results to another message queue, which is then processed by one or more workers. The job of these additional workers would be to pull summarization results from the queue and store them in the database. This is a possible solution but in our case it’s not really necessary to implement.

Once the results are in the database our front-end clients could use some mechanism that allows them to display these results to the customer who requested them. We will not get into more details about how exactly this will happen because it falls outside the scope of this system design exercise.

To finalize all that, here is the diagram with all the moving parts of our design. It should be able to scale well for the expected load and to allow to handle even more load. It should also be robust enough to let us deal with unexpected problems. As it usually is with system design interviews, it’s most likely possible to find flaws in this design. After all, we are supposed to come up with it within the matter of 30-40 minutes. The important thing is that it gives a solid base for a system that should work well in production and is detailed enough.